In recent years, Saturn and Jupiter have been in a moon race of their own. In 2019, Saturn took the lead with 20 new natural satellites, bringing its tally up to 82. Then Jupiter surged ahead to 92 in 2023. And later that year, Saturn reached 146, leaving Jupiter in a respectable second place position with 95.

But this week, Jupiter has truly been left in the dust. Astronomers have just announced the detection of an additional 128 moons, brining Saturn’s total to an eyewatering 274.

“This is a stunning increase in the number of known moons orbiting Saturn, a number which is always hard to keep up with,” says James O’Donoghue, a planetary astronomer at the University of Reading in England and who was not involved in the new discovery. “Jupiter is now very much in the rear-view mirror.”

But having a seemingly insurmountable record number of moons isn’t the most important part of the announcement. That’s because these 128 new satellites aren’t regular Saturnian moons, spheres of ice and rock whose orbits are closely aligned with the planet’s equator.

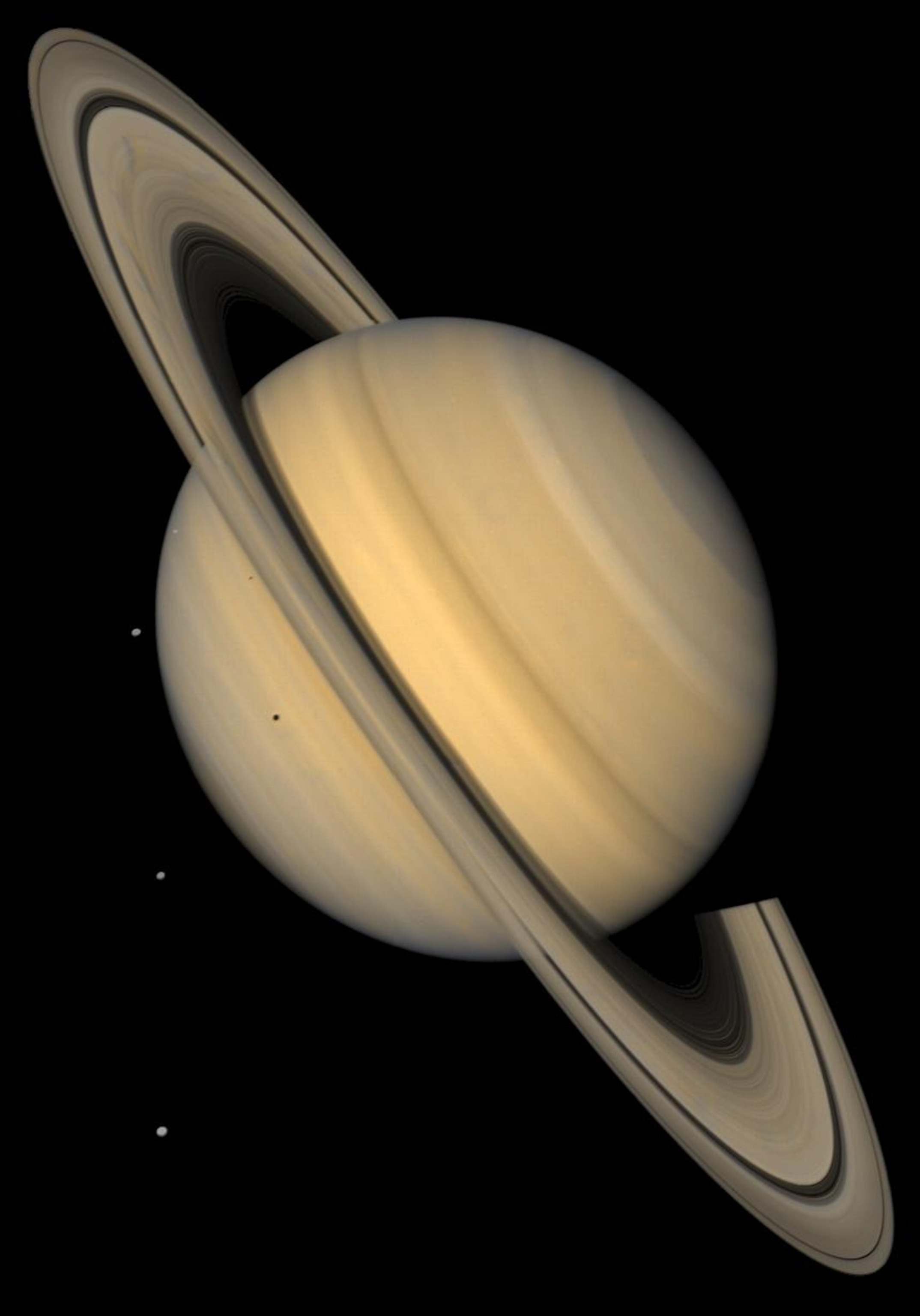

This approximate natural-color image shows Saturn, its rings, and four of its icy satellites. Three satellites (Tethys, Dione, and Rhea) are visible against the darkness of space, and another smaller satellite (Mimas) is visible against Saturn’s cloud tops very near the left horizon and just below the rings. The dark shadows of Mimas and Tethys are also visible on Saturn’s cloud tops, and the shadow of Saturn is seen across part of the rings.

Photograph by NASA/JPL/USGS

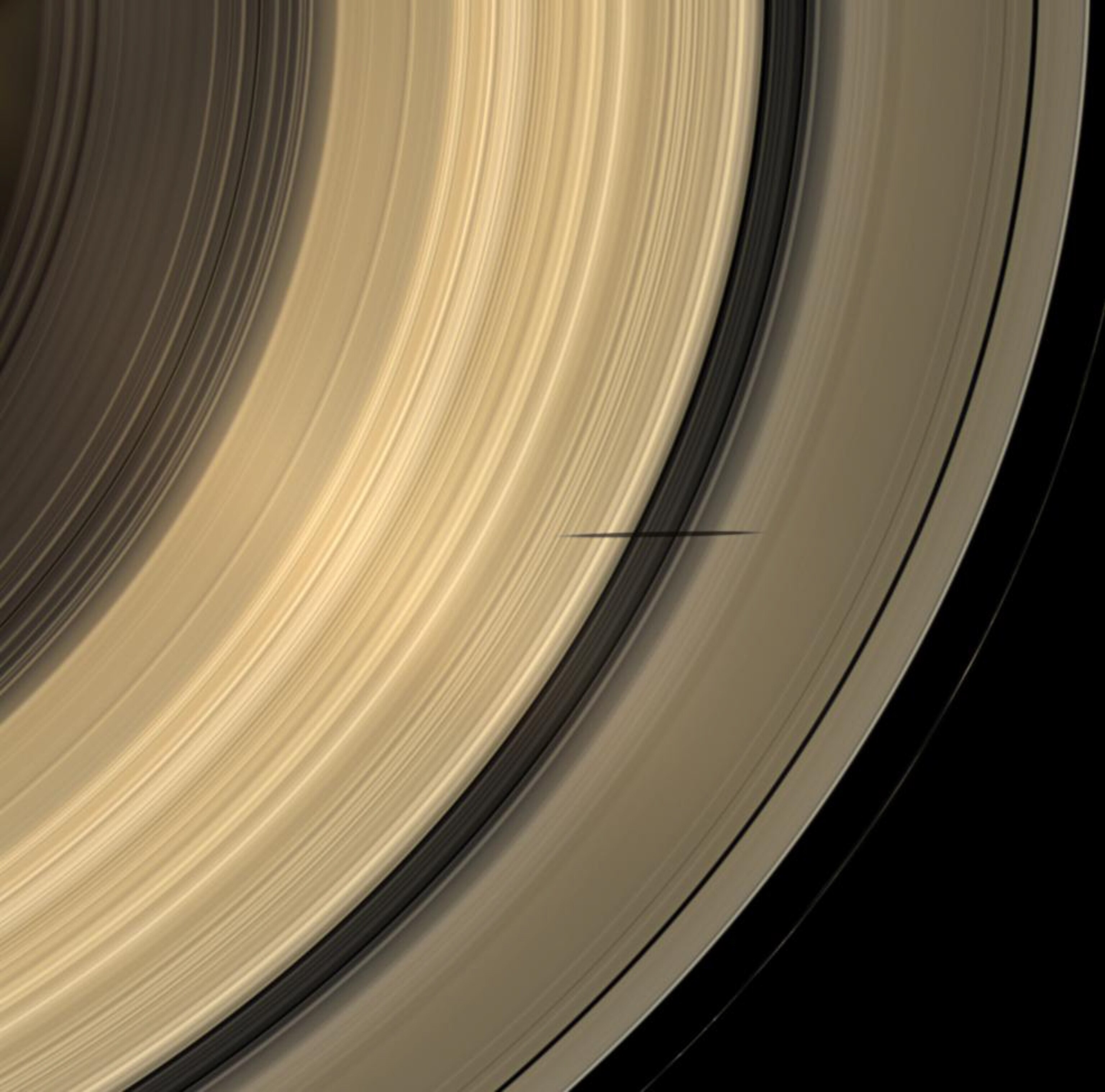

NASA’s Cassini spacecraft captures the shadow of Saturn’s moon Mimas as it dips onto the planet’s rings and straddles the Cassini Division in this natural color image.

Photograph by NASA/JPL/Space Science Institute

Instead, these lumpy objects, each just a few miles across, are known as irregular moons, so named because they are “on these wild orbits,” says Samantha Lawler, an astronomer at the University of Regina in Canada who wasn’t directly involved in the new research. They swing around the gas giant at steep angles, often in the opposite direction to Saturn’s own rotation.

These clues point toward a protracted destruction derby. Several billion years ago, larger voyagers made of rock and ice were captured by Saturn’s gravity, becoming moons in the process. Eventually, some of them smashed into one another, triggering a cascade of moon-on-moon violence that created hundreds of tinier, younger moons—each a fragment of their obliterated ancestors—that was still taking place as recently as 100 million years ago.

Inspiring exploration for over 130 years

Subscribe now a get a free tote

That makes finding 128 moons more than just cosmic bean counting. They are adding rich new detail to the chaotic history of the Saturnian system, a work-in-progress where nothing—from its moons to its resplendent rings—are permanent fixtures, but rather temporary decorations.

(Saturn’s ‘Death Star’ moon was hiding an underground ocean.)

Saturn shows off a ‘hilarious’ number of moons

All of Saturn’s moons vie for our attention. But several astronomers are particularly beguiled by Phoebe, a mid-sized moon discovered in 1898 and whose eccentric, backwards orbit has long marked it as irregular.

Today, Phoebe is in good company. Over the last few decades, plenty of smaller irregular moons have been detected, often using the Canada-France-Hawaii Telescope atop Hawai‘i’s dormant Mauna Kea volcano.

Saturn’s moon Rhea looms over a smaller and more distant Epimetheus against a striking background of planet and rings. The two moons aren’t actually close to each other.

Photograph by NASA/JPL/Space Science Institute

Saturn’s moon Mimas peeks out from behind the night side of the larger moon Dione in this image captured by NASA’s Cassini spacecraft during its flyby in December 2011.

Photograph by NASA/JPL-Caltech/Space Science Institute

The effects of the small moon Prometheus loom large on two of Saturn rings in this image taken by NASA Cassini spacecraft a short time before Saturn August 2009 equinox.

Photograph by NASA/JPL/Space Science Institute

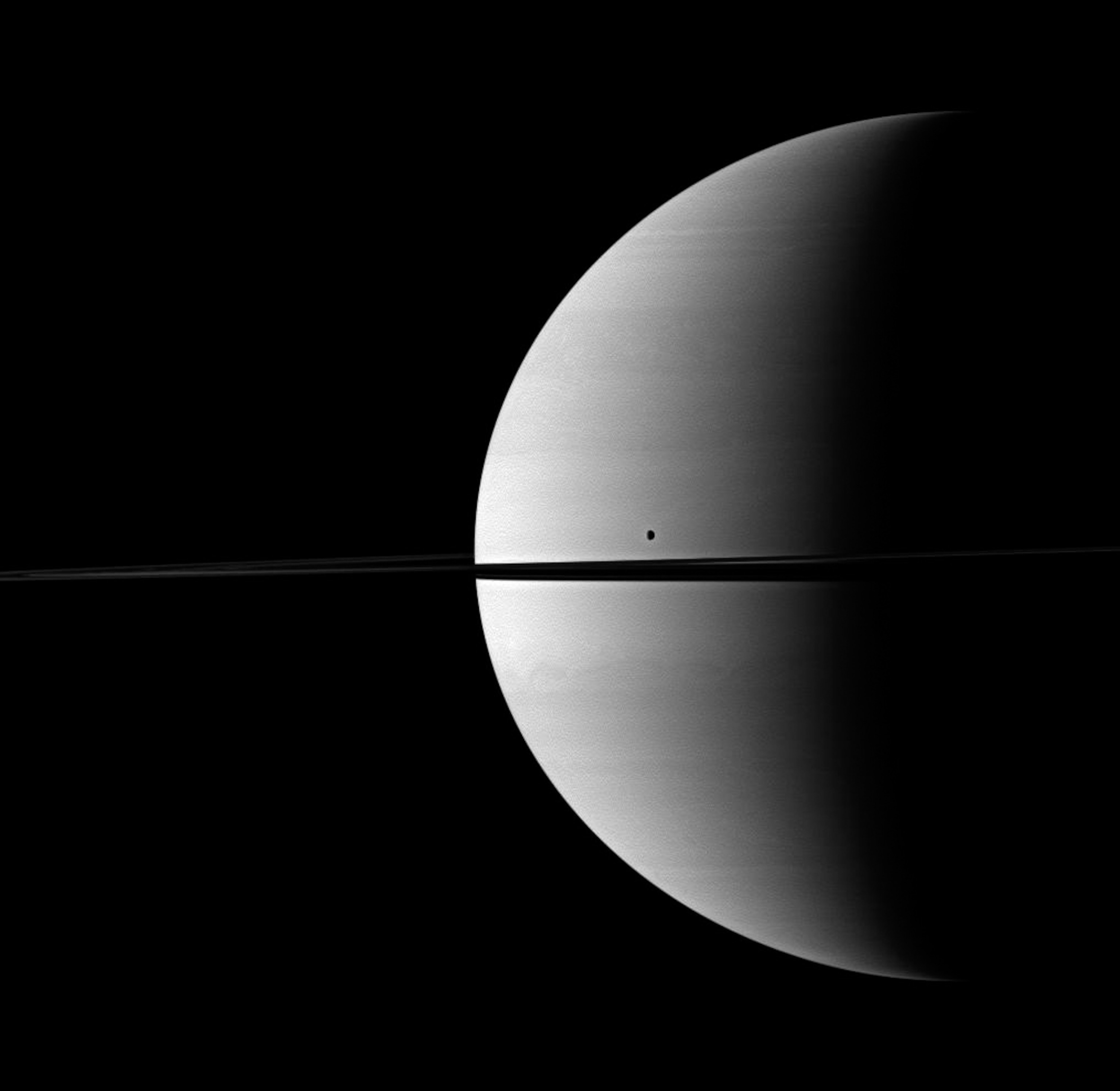

Saturn shares its space with its moon Tethys in this scene captured by NASA Cassini spacecraft. Tethys can be seen above the rings near the middle of the image. This view looks toward the northern, sunlit side of the rings from just above the ringplane.

Photograph by NASA/JPL/Space Science Institute

As far as anyone can tell, “Saturn has more moons than all the other planets put together,” says Brett Gladman, an astronomer at the University of British Columbia and one of several co-discoverers of the new moons.

Gladman and his colleagues have been responsible for finding many of them—and the more they’ve found, the more they’ve suspected that reams of even tinier moons were hiding in Saturn’s shadows, causing them to extend their quest.

The Minor Planet Center, based in Cambridge, Massachusetts, is a public noticeboard that lists all known small solar system objects. On a normal day, astronomers expect to see the discovery of a new comet or asteroid posted online. But on March 11, to the shock of many, the MPC revealed that 128 new Saturnian moons had been identified by Gladman’s team.

“I was blown away when I found out,” says Lawler. “That’s a lot. It’s hilarious.” (It also unequivocally means that Gladman has discovered or co-discovered more moons than anyone else in human history.)

“Not to be overlooked is the fact that Saturn is over a billion kilometers away from Earth, so it is amazing they can even be detected at all,” says O’Donoghue. At this point, it’s reasonable to wonder what the cutoff point is: When is a moon so tiny that it’s not a moon at all, but just a piece of ice or rock?

You May Also Like

In any event, these 128 objects have been officially recognized by the International Astronomical Union as moons. Gladman’s team now have the somewhat unusual problem of having to find names for each of them which, per convention, must be named after a figure in Gallic, Inuit or Norse mythology.

Suggestions are welcome. “This is altogether too many moons. How are we supposed to name them all?” says Paul Byrne, a planetary scientist at the Washington University in St. Louis not involved with the new discovery.

(Earth doesn’t have a second moon—but here’s what would happen if it did.)

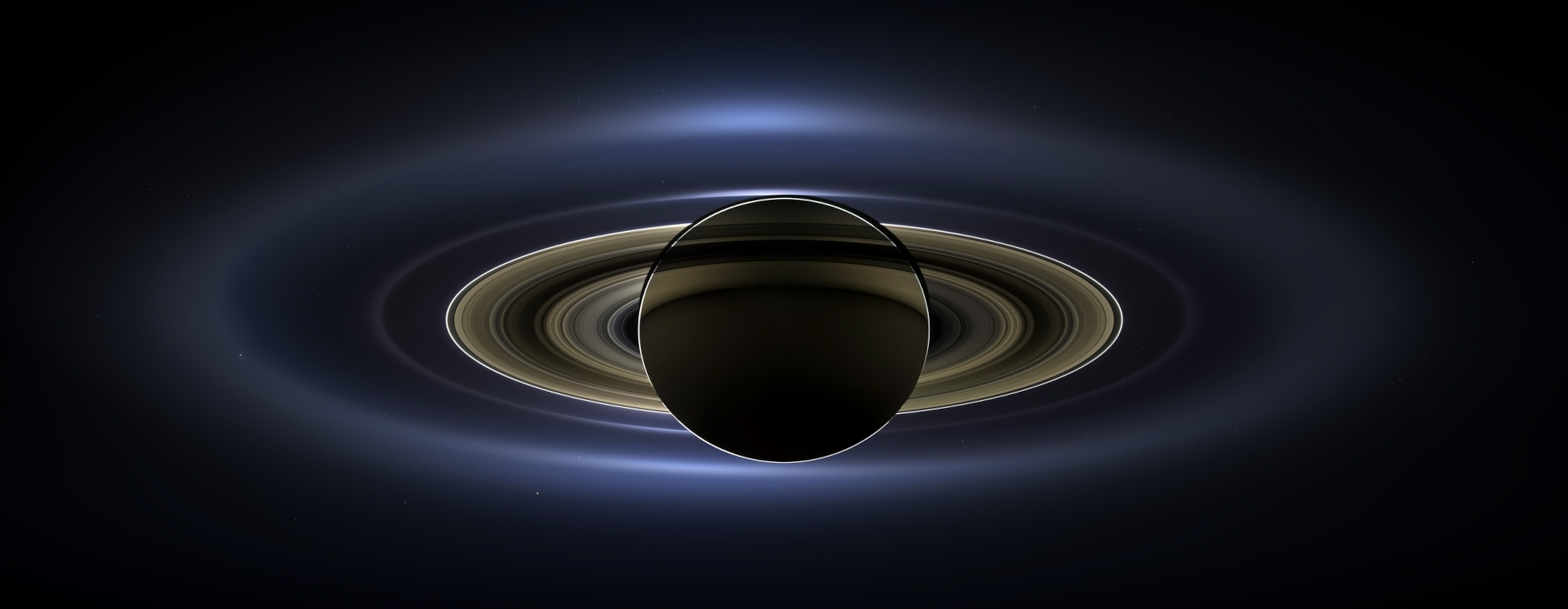

Cassini captured this image of Saturn’s shadow on the planet’s “dark side” on July 19, 2013. Visible are Saturn, seven of its moons, its inner rings, and in the background, our home planet, Earth. With the sun’s powerful and potentially damaging rays eclipsed by Saturn itself, Cassini’s onboard cameras were able to take advantage of this unique viewing geometry.

Composite Photograph by NASA/JPL-Caltech/SSI

What moons tell us about a planet’s history

None of these new moons are notable in isolation. But each is a piece taken from several now-broken jigsaws: some of the original moons of Saturn.

Certain irregular Saturnian moons are grouped into clusters, each named after their largest member. “Phoebe is like the lucky grandfather,” says Gladman. This heavily cratered moon has been impacted a lot, but it has nevertheless survived for several billion years. Today, it’s surrounded by its own cluster of smaller moons created by those older thwacks.

The Mundilfari cluster tells a different tale. It features such a high number of small moons that it cannot have ancient origins; many of these moons would have crashed into one other and vaporized themselves soon after they had formed. “We think this is a relatively recent collision,” says Gladman—the demolition of a larger moon sometime in the past 100 million years, practically last month by astronomic standards.

Saturn’s profusion of satellites also has implications for Jupiter. “Everyone agrees that Jupiter should have more moons,” says Lawler. But the gas giant’s proximity to Earth and expansive gravitational field can keep moons on the very edge of astronomers’ scopes, so its irregular satellites can be harder to spot.

Unlike Saturn, Jupiter lacks a youthful-looking moon cluster, Gladman notes. That suggests Jupiter hasn’t had a recent moon-on-moon collision, one that could have made a bevy of new, tiny satellites.

It also doesn’t look like any of Jupiter’s larger moons are going to crash into one another for the foreseeable future, which will leave Saturn the moon-collecting champion for a very long time to come. “I don’t think Jupiter’s ever going to catch it up,” says Gladman.